The last few days have been soul-destroying for anyone who believes in the need for mutual tolerance and understanding. Brazil elected a new far-right president with a long history of hateful views against women, homosexuals, minorities, and immigrants. Germany witnessed another surge in Far Right support in a state election. A synagogue in Pittsburgh was the site of probably the most deadly attack on the Jewish community in US history, at the hands of a white supremacist gunman shouting “all Jews must die.” Donald Trump dubbed a large group of Central Americans fleeing gang violence, corruption, and drought “an invasion,” vowing to use the US army to fight them back at a possibly closed southern border.

It is easy to feel hopeless in the face of a seemingly dramatic rise in hatred and intolerance around the world. In an effort to relieve myself of these feelings, if only temporarily, I decided today that as a musician, music researcher, and music teacher, I needed to remind myself of music’s potential as a force for good amidst the madness.

These days, we tend to think of music as primarily a source of entertainment and distraction. Beyond this, we think of it as a means to sooth, calm, and relax. Certainly we need all these things from music in these challenging times. But music can do so much more than this. Music can empower. Music can unify. Music can help us resist hatred by creating community.

In an era of profound individualism, where we spend so much of our time alone in front of screens, music can help us reconnect. It reminds us what community feels like, what togetherness and unity of purpose feels like–both oddly uncommon experiences in our times.

In North America, when we think of music being put to political ends, we typically think first of the protest songs of the Civil Rights era. Civil Rights leaders used music effectively to create a unity of purpose and to defuse white-American anxieties about black American resistance. No group of peaceful marchers could be convincingly labeled an angry mob as they linked arms and sang “We Shall Overcome.”

Songs like this are still heard frequently in twenty-first century protests. But today’s resisters could use some new tunes and some new musical strategies to unify their cause. Students protesting university fee increases in 2012 Quebec knew this, and so brought their own powerful sonic tool to their marches. The pots and pans they banged became a collective outlet for their frustration – a way to “make noise” about their concerns in a way that no-one could ignore.

But musical resistance goes far beyond the protest march. Music can unify anti-oppression movements at the ground level. My own research has recently led me to El Salvador, to study the music-making of refugees from that country’s terrible Civil War in the 1980s. Peasant farmers rose up to resist an oppressive right-wing government, only to be brutally suppressed by their nation’s own US-backed army. I’ve been helping to gather folk songs from former refugees, who sang powerfully of their will to resist their government’s oppression. In the Honduran camps where many of them lived for much of the war, music helped refugees living in dire circumstances to document their army’s massacres, to process what was happening to them collectively, and to articulate their right to a better government.

Music has been used in these ways all over the world for centuries. Either overtly or abstractly, it can help us as humans to process our very worst experiences. It can give us hope where it feels like none exists.

Such hopefulness inspired a powerful musical bridge-building enterprise for the Middle East: the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. This ensemble was created by Daniel Barenboim and the late Edward Said in 1999. It brought together Israeli, Palestinian, and other Arab orchestral musicians. The orchestra’s goal, they said, was “to replace ignorance with education, knowledge and understanding; to humanize the other; to imagine a better future.” Said and Barenboim’s efforts have not ended this intractable conflict, of course. But they give hope, and they provide the seeds for greater understanding through collaboration and conversation.

Over in the UK, British-Asian musicians similarly used music across an ethnic divide to help fight the rising influence of the British National Party and a corresponding increase of violence against young Asian men. The documentary below tells their story. In concerts of overtly anti-fascist music, they bring an uplifting message to a disillusioned younger generation looking to connect and find hope. They also run workshops that give young British Asians living in poverty-stricken East London access to tools for musical composition and performance, granting those that might choose to fight their oppression with violence a different, more constructive outlet for their frustrations.

Indigenous peoples across the world have for centuries used their traditional musics as a tool to resist colonial oppression, and this continues today. Music was central to the protests at Standing Rock, where indigenous and environmental protesters gathered to resist the building of the Dakota access pipeline across native lands. Here in Canada, the Idle No More movement used music particularly effectively to make a case for indigenous rights and sovereignty. This song came to serve as a theme song for that movement.

Non-indigenous artists have added their own musical contributions to aid these efforts. But this leaves me wondering: where are the mainstream expressions of a constructive shared identity? Can the music of the non-indigenous and anti-fascist majority in the West find a mode of musical expression that celebrates identity in common cause just as effectively? Can we imagine popular music, by popular musicians, that gives voice to an anti-fascist celebration of multiculturalism? And can us non-famous musicians put our musical skills to good use by creating new mechanisms to establish the kinds of cross-cultural conversations that help build community and fight hatred?

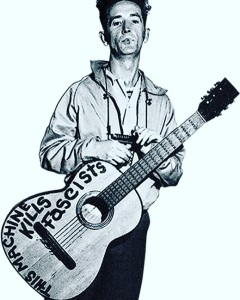

Many mainstream pop musicians avoid such moves, presumably concerned about limiting their “brand.” The public’s surprise at Taylor Swift’s recent decision to declare her support for the Democrats demonstrates how widespread this tendency has become. But North America and Europe have a long, compelling history of using music to build connections and resist oppression and discrimination. Maybe the time has come to start applying our many great models for musical anti-fascism to a much wider array of contexts.